Islet Cell Transplantation: Type 1 Diabetes Cure May be Close to Reality

A new study found that human islet cell (cell clusters that contain insulin-producing cells) transplantation may prevent severe, potentially life-threatening drops in blood sugar in people with type 1 diabetes and provide excellent blood sugar control for patients with Type 1 diabetes with severe hypoglycemia.

The results of the multi-center, single arm, phase III study are published in Diabetes Care on Monday, April 18. The research was funded by National Institute of Health (NIH) grants through the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) and the National Institute for Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease (NIDDK).

Risk of Hypoglycemia in Type 1 Diabetes

In type 1 diabetes, the immune system attacks and destroys insulin-producing cells in the islets of the pancreas. People with type 1 diabetes need lifelong treatment with insulin, which helps transport the sugar glucose from the bloodstream into cells, where it serves as a key energy source. Even with insulin therapy, people with type 1 diabetes frequently experience fluctuations in blood sugar levels.

Hypoglycemia or low blood sugar, typically is accompanied by symptoms such as tremors, sweating and heart palpitations that prompt people to eat or drink to raise their blood sugar levels. Those who do not experience these early warning signs — a condition called impaired awareness of hypoglycemia — are at increased risk for severe hypoglycemic events, during which the person is unable to treat himself or herself. Treatments such as behavioral therapies or continuous glucose-monitoring systems can prevent these events in many — but not all — people with this impaired awareness, leaving a substantial number of people at risk.

Islet Cell Transplantation For People with Type 1 Diabetes

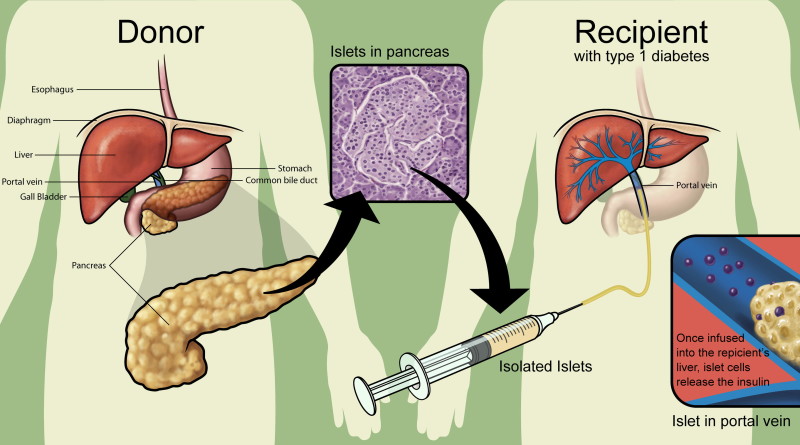

Islet transplantation is an investigational therapy for individuals with Type 1 diabetes in which islet cells from a donor pancreas are transplanted into another person. In patients with diabetes, the pancreas does not properly produce insulin. Using a minimally invasive radiologic technique, islet transplantation infuses working cells that can control blood glucose and possibly eliminate the need for insulin therapy. Islets begin to release insulin soon after transplantation with increased function occurring over time.

“The findings suggest that for people who continue to have life-altering severe hypoglycemia despite optimal medical management, islet transplantation offers a potentially lifesaving treatment that in the majority of cases eliminates severe hypoglycemic events while conferring excellent control of blood sugar,” said NIAID Director Anthony S. Fauci, M.D.

The current study enrolled 48 people who had persistent impaired awareness of hypoglycemia and experienced severe hypoglycemic events despite expert care by a diabetes specialist or endocrinologist. Investigators at eight study sites in North America used a standardized manufacturing protocol to prepare purified islets from the pancreases of deceased human donors. All study participants received at least one transplant of islets injected into the portal vein, the major vessel that carries blood from the intestine into the liver. Islet recipients currently must take immunosuppressive drugs for the rest of their lives to prevent their immune systems from rejecting the transplanted cells.

One year after the first transplant, 88 percent of study participants were free of severe hypoglycemic events, had established near-normal control of glucose levels, and had restored hypoglycemic awareness. After two years, 71 percent of participants continued to meet these criteria for transplant success.

Even a small number of functioning, insulin-producing cells can restore hypoglycemic awareness, although transplant recipients may need to continue taking insulin to fully regulate blood glucose levels. Participants who still needed insulin 75 days after transplant were eligible for another islet infusion. Twenty-five participants received a second transplant, and one received three. After one year, 52 percent of study participants no longer needed insulin therapy.

As expected, the treatment carried risks, including infections and lowered kidney function as a result of people taking the immune-suppressing drugs needed to prevent rejection of the donor islets. Although some of the side effects were serious, none led to death or disability. In the United States, islet transplantation is currently available only in clinical trials.

- Adolescents Living With Diabetes - August 6, 2022

- Diabetes Insipidus Symptoms, Causes, & Prevention - July 26, 2022

- Insulin Shortage May Affect Almost Half of the Diabetics by 2030 - November 24, 2018

Pingback: Melissa Tower (melissatower) | Pearltrees